Language is a map of cultural development.

It tells how the people appeared and in what direction they are developing.

Rita Mae Brown

Very often, starting a study becomes problematic for linguists, since even the beginning must already have some kind of background. The paths of the past lead to the present. Sometimes a scientific approach to research origin of the ancient language is purely hypothetical.

To establish origin of the language we need theoretical foundations and the basic structure of the language. In the case of the Armenian language, the hypothesis is based on its relationship to the Indo-European family, which, in addition to Armenian, includes more than 100 languages. The basic structure of a language is established through the analysis of words and sounds that go back to the common roots of the Indo-European proto-language. The study of language regarding its origin and evolution is mainly related to its speech characteristics. Most modern linguists in their work rely on the hypothesis that spoken language is more fundamental, and therefore more important, than written language. Thus, The Armenian language is considered primarily a descendant of the Indo-Hittite group of languages. Linguists who support the belonging of the Armenian language to the Indo-European family of languages agree that this language constitutes a separate branch within the group.

From the very beginning, several hypotheses were put forward. European linguists of past centuries made attempts to explore and classify this language. Mathurin Veyssières de Lacroze(La Croze) (fr. Mathurin Veyssière de La Croze 1661-1739) became one of the first European scientists of the modern era to seriously study Armenian language research, namely its religious side. The linguist wrote that the translation of the Bible into Armenian is “sample of all translations.” Mathurin Veyssier de Lacroze compiled an impressive German-Armenian dictionary (approximately 1802 entries), but he limited himself to studying only lexicology, without delving into the origins of the language.

Immediately after the principles of comparative linguistics were outlined Franz Bopp (Franz Bopp), Petermann in his work " GrammaticalinguaeArmeniacae» (Berlin, 1837), based on etymological data on the Armenian language available in Germany at the beginning of the 19th century, was able to hypothesize that Armenian language belongs to the Indo-European family of languages. Nine years later in 1846, independent of Petermann's research, Windischmann- specialist on Zoroastrian inscriptions of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences - published in his scientific work Abhandlungen a remarkable monograph on the Armenian language, which concluded that the Armenian language originated from an ancient dialect that must have been very similar to Avestan language(the language in which the Zoroastrian manuscripts were written) and Old Persian, in which, however, borrowings appeared much earlier.

Along with how Pott expressed doubts regarding the genetic relationship of Armenian with Aryan languages, and allowed only a significant influence of the latter on the former, Diefenbach, on the contrary, noted that this hypothesis is not sufficient to explain the close relationship between Armenian and Indian/Sanskrit and Old Persian languages. Adopted the same point of view Gaucher (Gosche) in his dissertation: “ DeArianalinguaegentisqueArmeniacaeindole» (Berlin, 1847). Three years later in the periodical " ZeitschriftderDeutschenMorgenlä ndischenGesellschaft» , under the title “Vergleichung der armenischen consonanten mit denen des Sanskrit,” de Lagarde published the results of his work: a list of 283 Armenian words with their etymological definitions, where the characteristics of the language itself were not touched upon in detail.

In the preface to the second edition " Comparative Grammar"(1857) Bopp, a pioneer in the field of comparative linguistics research, classified the Armenian language as Iranian group and made an attempt, albeit unsuccessful, to explain the inflectional elements in language. Fr.Müller, which since 1861 engaged in etymological and grammatical research Armenian language in a series of his scientific articles ( SitzungsberichtederWienerAcademy), was able to penetrate much deeper into the essence of the Armenian language, which in his opinion definitely belonged to the Iranian group.

Russian linguist Patkanov following the German orientalists, he published his final work “Über die bildung der armenischen sprache” (“ About the structure of the Armenian language"), which was translated from Russian into French and published in " JournalAsiatique» (1870). De Lagarde in his work GesammeltenAbhandlungen(1866) argued that three components should be distinguished in the Armenian language: the original stem, subsequent superimpositions of the ancient Iranian language, and similar modern Iranian loanwords that were added after the founding of the Parthian State. However, he did not characterize all three levels, and for this reason his opinion cannot be accepted for further consideration. Muller’s point of view that the Armenian language is a branch of the Iranian group of languages was not refuted at the time, turned out to be prevalent and formed the basis of the theory.

Significant shift away from Persian theories was made after the appearance of the monumental work authored Heinrich Hubschmann (HeinrichHü bschmann), in which, as a result of extensive research, it was concluded that the Armenian language belongs to Aryan-Balto-Slavic languages, or more precisely: it is an intermediate link between the Iranian and Balto-Slavic languages. The linguist's in-depth study of the Armenian language influenced the reassessment of the kinship of languages within the Indo-European family, and the optimization of its schematic classification. The Armenian language is not just an independent element in the chain of Aryan-Persian and Balto-Slavic languages, but it is a connecting link between them. But if the Armenian language is a connecting element between the Iranian and Balto-Slavic languages, between Aryan and European, then, according to Hübschmann, it should have played the role of an intermediary at a time when all these languages were still very close to each other, when not yet there were clear boundaries between them, and when they could only be considered as dialects of one language.

Later, almost as an exception, Hübschmann continued his research into the Armenian language and published several books on the topic. Later linguists and experts on Indo-European languages strengthened Hübschmann's conclusions and continued this research. Swiss linguist Robert Godel and some of the most eminent linguists or specialists in the study of Indo-European languages ( Emile Benveniste, Antoine Meillet and Georges Dumezil) a lot has also been written about various aspects of Armenian etymology and the Indo-European origin of this language.

It is not surprising that others also came forward theories about the origin of the Armenian language. Sharply different from the theory of the Indo-European origin of the Armenian language hypothesis Nikolai Yakovlevich Marr about his Japhetic origin(named Japheth, the son of Noah), based on certain phonetic features of the Armenian and Georgian languages, which in his opinion originated from the same language family, Japhetic, having a connection with the Semitic family of languages.

Between supporters Kurgan hypothesis and the Semitic theory of the origin of languages, there are a number of linguists who also consider the possibility of the spread of languages from the territory of Armenia. This hypothesis refutes the widely held belief about the Central European origin of languages. Recently, new research in this direction led to the formulation by Paul Harper and other linguists of the so-called glottal theory, which is perceived by many experts as an alternative to the theory of the Indo-European origin of languages.

In addition to the dubious theory of the Persian origin of the languages, the Armenian language is often characterized as a close relative of the Greek language. And yet, none of these hypotheses is regarded as sufficiently serious from a purely philological point of view. Armenian philologist Rachiya Akopovich Acharyan compiled an etymological dictionary of the Armenian language, containing 11,000 root words of the Armenian language. Of this total, Indo-European root words make up only 8-9%, borrowed words - 36%, and a predominant number of “undefined” root words, which make up more than half of the dictionary.

A significant number of “undefined” root words in the Armenian language (almost 55% of the vocabulary) is an obvious sign of the “unexplained” origin of the language, which contradicts the traditional classification and/or genetic relationship with neighboring Greek or Persian cultures. It might be more reasonable to investigate the genetic connection along etymological lines with the extinct languages (Hurrian, Hittite, Luwian, Elamite or Urartian) that existed in the territory of modern Armenia (the Anatolia and Eastern Turkey regions.)

Experts in the study of Indo-European languages agree that the Proto-Indo-European division of languages began in the 4th millennium BC, which gave impetus to linguistic evolution and the formation of independent languages. Likewise, ok. 3500 BC proto-Armenian tribes-whether they were European in origin (according to the Thraco-Phrygian theory supported by Western scholars) or Asian (Aryan/Aboriginal/other Asian tribes) - created an economic structure based on agriculture, animal husbandry and metalworking in a geographical area that became known as Armenian Highlands.

The results of recent archaeological research in Armenia have provided evidence of several similarities between this civilization and Indo-European culture. With a high degree of probability, it can be assumed that the Armenian culture is original and stood apart from other human cultures in Asia Minor and Upper Mesopotamia.

In this context, the Armenian language, with continuous evolution and unchanged geographical location, continued to develop and enrich itself at the expense of neighboring cultures, as evidenced by the presence of borrowed words, and after the creation of writing, exchange experiences with other distant cultures. Thus, it can be assumed that the history of the Armenian language and its modern version goes back approximately 6,000 years.

It is likely that such a divergence of linguistic theories pursues one goal - to better understand the nature of the Armenian language. Behistun inscriptions in Central Iran 520 BC often cited as the first mention of the word Armenia . In this regard, for many, including historians, the history of the Armenians begins with the 6th century BC. And yet, such a “beginning of history” is an arbitrary and superficial conclusion. The fact that in the Behistun written monument the event is described in three different languages is not attached or ignored: Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian. What is true is that the oldest record mentioning the word “Armenia” is in cuneiform.

Armenian language ()- The Indo-European language is usually classified as a separate group, less often combined with Greek and Phrygian. Among the Indo-European languages, it is one of the oldest written languages. The Armenian alphabet was created by Mesrop Mashtots in 405-406. The total number of speakers around the world is about 6.7 million people. During its long history, the Armenian language has been in contact with many languages. Being a branch of the Indo-European language, Armenian subsequently came into contact with various Indo-European and non-Indo-European languages - both living and now dead, taking over from them and bringing to the present day much of what direct written evidence could not preserve. At different times, Hittite and hieroglyphic Luwian, Hurrian and Urartian, Akkadian, Aramaic and Syriac, Parthian and Persian, Georgian and Zan, Greek and Latin came into contact with the Armenian language. For the history of these languages and their speakers, data from the Armenian language are in many cases of paramount importance. This data is especially important for urartologists, Iranianists, and Kartvelists, who draw many facts about the history of the languages they study from Armenian.

Armenian is one of the Indo-European languages, forming a special group of this family. Number of speakers - 6.5 million. Distributed in Armenia (3 million people), USA and Russia (1 million each), France (250,000), Georgia, Iran, Syria (200,000 each), Turkey, Azerbaijan (150,000 each), Lebanon , Ukraine (100,000 each), Argentina (70,000), Uzbekistan (50,000) and other countries.

It belongs to the group of Indo-European languages, among which it is one of the ancient written ones. The history of the literary Armenian language is divided into 3 periods: ancient, middle and new. Ancient - from 5th to 11th centuries. The language of this period is called ancient Armenian, and the language of written monuments is called Grabar. The language of the middle period (11th-17th centuries) is called Middle Armenian. The new period (from the 17th century) is characterized by the formation of modern A. Ya., which already from the end of the 19th century. acquires the features of the New Armenian literary language. It is represented by eastern and western variants, divided into many dialects. The population of Armenia uses the eastern version - Ashkharabar.

The Armenian language began to be formed, in all likelihood, already in the 7th century. BC, and its Indo-European elements were layered on the language of the ancient population of Armenia, alien to it from time immemorial - the Urartians (Chaldians, Alarodians), preserved in the so-called Van cuneiform.

Most scientists (cf. Prof. P. Kretschmer, “Einleitung in die Geschichte d. Griechischen Sprache”, 1896) believe that this stratification was the result of an invasion of the foreign language region of Armenia by a people who were a group that broke away from the Thracian-Phrygian branch of the Indo -European languages.

The separation of the future “Armenian” group was caused by the invasion (in the second half of the 8th century BC) of the Cimmerians into the territory occupied by the Phrygian people. This theory is based on the news conveyed by Herodotus (Book VII, Chapter 73) that “the Armenians are a colony of the Phrygians.”

In the Baghistan inscription of Darius I, son of Hystaspes, both Armenians and Armenia are already mentioned as one of the regions that were part of the ancient Persian Achaemenid monarchy. The formation of the Armenian language took place through assimilation, to which the languages of the old population of the future Armenia were subjected.

In addition to the Urartians (Chaldians, Alarodians), the Armenians, during their consistent advance in the eastern and northeastern directions, undoubtedly assimilated into a number of other nationalities. This process occurred gradually over several centuries. Although Strabo (book XI, chapter 14) reports that in his time the peoples that were part of Armenia spoke the same language (“were monolingual”), one must think that in some places, especially on the peripheries, continued to survive native speech.

Thus, the Armenian language is a language of a mixed type, in which native non-Indo-European linguistic elements were combined with the facts of the Indo-European speech of the new colonizer-conquerors.

These non-Indo-European elements dominate mainly the vocabulary. They are comparatively less noticeable in grammar [see. L. Mseriants, “On the so-called “Van” (Urartian) lexical and suffixal elements in the Armenian language.”, M., 1902]. According to academician N. Ya. Marr, the non-Indo-European part of the Armenian language, revealed under the Indo-European layer, is related to the Japhetic languages (cf. Marr, “Japhetic elements in the language of Armenia”, Publishing House of Academy of Sciences, 1911, etc. work).

As a result of linguistic mixing, the Indo-European character of the Armenian language has undergone significant modifications both in grammar and vocabulary.

About the fate of the Armenian language until the 5th century. after the RH we have no evidence, with the exception of a few individual words (mainly proper names) that came down in the works of the ancient classics. Thus, we are deprived of the opportunity to trace the history of the development of the Armenian language over thousands of years (from the end of the 7th century BC to the beginning of the 5th century after the AD). The language of the wedge-shaped inscriptions of the kings of Urartu or the Kingdom of Van, which was replaced by Armenian statehood, genetically has nothing in common with the Armenian language.

We become familiar with ancient Armenian through written monuments dating back to the first half of the 5th century. after the Russian Empire, when Mesrop-Mashtots compiled a new alphabet for the Armenian language. This ancient Armenian literary language (the so-called “grabar”, that is, “written”) is already integral in grammatical and lexical terms, having as its basis one of the ancient Armenian dialects, which has risen to the level of literary speech. Perhaps this dialect was the dialect of the ancient Taron region, which played a very important role in the history of ancient Armenian culture (see L. Mseriants, “Studies on Armenian dialectology,” part I, M., 1897, pp. XII et seq.). We know almost nothing about other ancient Armenian dialects and only get acquainted with their descendants already in the New Armenian era.

Ancient Armenian literary language (" grabar") received its processing mainly thanks to the Armenian clergy. While the "grabar", having received a certain grammatical canon, was kept at a certain stage of its development, living, folk Armenian speech continued to develop freely. In a certain era, it enters a new phase of its evolution, which is usually called Central Armenian.

The Middle Armenian period is clearly visible in written monuments, starting only from the 12th century. Middle Armenian for the most part served as the organ of works intended for a wider range of readers (poetry, works of legal, medical and agricultural content).

In the Cilician period of Armenian history, due to the strengthening of urban life, the development of trade with the East and West, relations with European states, the Europeanization of the political system and life, folk speech became an organ of writing, almost equal to classical ancient Armenian.

A further step in the history of the evolution of the Armenian language. represents New Armenian, which developed from Middle Armenian. He received citizenship rights in literature only in the first half of the 19th century. There are two different New Armenian literary languages - one “Western” (Turkish Armenia and its colonies in Western Europe), the other “Eastern” (Armenia and its colonies in Russia, etc.). Middle and New Armenian differ significantly from Old Armenian both in grammatical and vocabulary terms. In morphology we have many new developments (for example, in the formation of the plural of names, forms of the passive voice, etc.), as well as a simplification of the formal composition in general. The syntax, in turn, has many peculiar features.

There are 6 vowels and 30 consonant phonemes in the Armenian language. A noun has 2 numbers. In some dialects, traces of the dual number remain. Grammatical gender has disappeared. There is a postpositive definite article. There are 7 cases and 8 types of declension. A verb has the categories of voice, aspect, person, number, mood, tense. Analytical constructions of verb forms are common. The morphology is predominantly agglutinative, with elements of analytism.

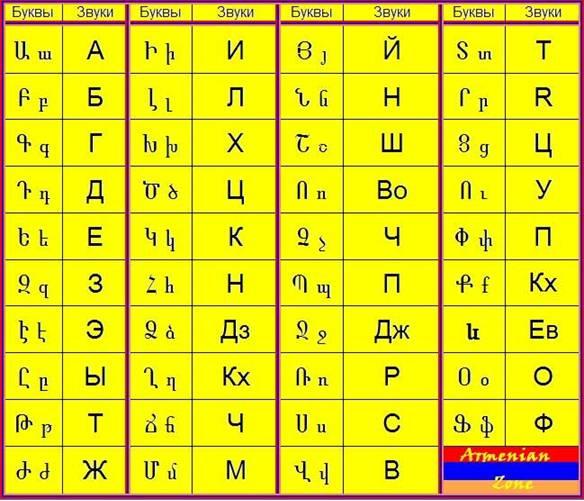

Armenian sound writing, created by an Armenian bishop Mesrop Mashtots

based on Greek (Byzantine) and Northern Aramaic script. Initially, the alphabet consisted of 36 letters, 7 of which conveyed vowels, and 29 letters represented consonants. Around the 12th century, two more were added: a vowel and a consonant.

Modern Armenian writing includes 39 letters. The graphics of the Armenian letter have historically undergone significant changes - from angular to more rounded and cursive forms.

There are good reasons to believe that its core, dating back to ancient Semitic writing, was used in Armenia long before Mashtots, but was banned with the adoption of Christianity. Mashtots was, apparently, only the initiator of its restoration, giving it state status and the author of the reform. The Armenian alphabet, along with Georgian and Korean, is considered by many researchers to be one of the most perfect.

Essay on the history of the Armenian language.

The place of the Armenian language among other Indo-European languages has been the subject of much debate; it has been suggested that Armenian may be a descendant of a language closely related to Phrygian (known from inscriptions found in ancient Anatolia).

The Armenian language belongs to the eastern (“Satem”) group of Indo-European languages and shows some similarities with the Baltic, Slavic and Indo-Iranian languages. However, given the geographical location of Armenia, it is not surprising that Armenian is also close to some Western (“centum”) Indo-European languages, primarily Greek.

The Armenian language is characterized by changes in the field of consonantism, which can be illustrated by the following examples: Latin dens, Greek o-don, Armenian a-tamn “tooth”; lat. genus, Greek genos, Armenian cin "birth". The advancement in Indo-European languages of stress on the penultimate syllable led to the disappearance of the stressed syllable in the Armenian language: Proto-Indo-European bheret turned into ebhret, which gave ebr in Armenian.

The Armenian ethnic group was formed in the 7th century. BC. on the Armenian Highlands.

In the history of the Armenian written and literary language, there are 3 stages: ancient (V-XI centuries), middle (XII-XVI centuries) and new (from the 17th century). The latter is represented by 2 variants: western (with the Constantinople dialect as the basis) and eastern (with the Ararat dialect as the basis).

The Eastern variant is the language of the indigenous population of the Republic of Armenia, located in the eastern region of historical Armenia, and part of the Armenian population of Iran. The eastern version of the literary language is multifunctional: it is the language of science, culture, all levels of education, the media, and there is a rich literature in it.

The Western version of the literary language is widespread among the Armenian population of the USA, France, Italy, Syria, Lebanon and other countries, immigrants from the western part of historical Armenia (the territory of modern Turkey). In the Western version of the Armenian language, there is literature of various genres, it is taught in Armenian educational institutions (Venice, Cyprus, Beirut, etc.), but it is limited in a number of areas of use, in particular in the field of natural and technical sciences, which are taught in the main languages of the corresponding regions.

The phonetics and grammar features of both variants are considered separately. As a result of centuries-old Persian domination, many Persian words entered the Armenian language. Christianity brought with it Greek and Syriac words. The Armenian lexicon also contains a large proportion of Turkish elements that penetrated during the long period when Armenia was part of the Ottoman Empire. There are also a few French words left, borrowed during the era of the Crusades.

The oldest written monuments in the Armenian language date back to the 5th century. One of the first is the translation of the Bible into the “classical” national language, which continued to exist as the language of the Armenian Church, and until the 19th century. was also the language of secular literature.

History of the development of the Armenian alphabet

The history of the creation of the Armenian alphabet is told to us, first of all, by one of Mashtots’ favorite students, Koryun, in his book “The Life of Mashtots” and Movses Khorenatsi in his “History of Armenia”. Other historians have used their information. From them we learn that Mashtots was from the village of Khatsekats in the Taron region, the son of a noble man named Vardan. As a child, he studied Greek literacy. Then, arriving at the court of Arshakuni, the kings of Great Armenia, he entered the service of the royal office and was the executor of the royal orders. The name Mashtots in its oldest form is referred to as Majdots. The famous historian G. Alishan derives it from the root "Mazd", which, in his opinion, "should have had a sacred meaning." The root "mazd", "majd" can be seen in the names Aramazd and Mazhan (Mazh(d)an, with the subsequent drop of the "d"). The last name is mentioned by Khorenatsi as the name of the high priest.

It seems to us that A. Martirosyan’s assumption is correct that “the name Mashtots apparently comes from the preferences of the priestly-pagan period of his family. It is known that after the adoption of Christianity by the Armenians, the sons of the priests were given into the service of the Christian church. The famous Albianid family (church dynasty in Armenia - S.B.) was of priestly origin. The Vardan clan could have been of the same origin, and the name Mashtots is a relic of the memory of this." It is undeniable that Mashtots came from a high class, as evidenced by his education and activities at the royal court.

Let us now listen to the testimony of Koryun: “He (Mashtots) became knowledgeable and skilled in worldly orders, and with his knowledge of military affairs he won the love of his warriors... And then,... renouncing worldly aspirations, he soon joined the ranks of hermits. After some time he and his students went to Gavar Gokhtn, where, with the assistance of the local prince, he again converted those who had departed from the true faith into the fold of Christianity, “rescuing everyone from the influence of the pagan traditions of their ancestors and the devilish worship of Satan, bringing them into submission to Christ.” This is how his main activity begins , so he entered church history as the second enlightener.To understand the motives of his educational activities, and then the motives for creating the alphabet, one must imagine the situation in which Armenia found itself at that period of its history, its external and internal atmosphere.

Armenia at that time was between two strong powers, the Eastern Roman Empire and Persia. In the 3rd century in Persia, the Arsacids were replaced by the Sassanid dynasty, which intended to carry out religious reform. Under King Shapukh I, Zoroastrianism became the state religion in Persia, which the Sassanids wanted to forcefully impose on Armenia. The answer was the adoption of Christianity by the Armenian king Trdat in 301. In this regard, A. Martirosyan accurately notes: “The conversion of Armenia to Christianity at the end of the 3rd and beginning of the 4th centuries was a response to the religious reform of Iran. In both Iran and Armenia they were introduced by special royal decrees, as an act of political will. In the first case, religion dictated aggression, in the second resistance."

In 387, Armenia was divided between Byzantium and Persia. The Armenian people did not want to put up with this situation. The Armenian Arsacid dynasty sought to restore the integrity of its kingdom. At that time, her only ally was the church, since the Naharars, being strong individually, waged internecine hostility. Thus, the church was the force that could, by becoming a mediator between the nakharars, raise the people.

At this time, the idea of nationalizing Christianity was born. After all, Christianity, which came to Armenia from Mesopotamia under Hellenistic conditions, was in an alien language and incomprehensible to the people. There was a need for national Christian literature in the native language so that it would be understandable to the people. If for a whole century after the adoption of Christianity the church did not need a national written language due to its cosmopolitan nature, then in the new conditions, after the division of the country, the role of the church changed. At this time, it sought to nationalize in order to become a consolidating core in society. It was at this time that the need for a national written language arose.

Thus, the political situation in Armenia forced Mashtots to leave his service at court and become a hermit. He commissioned works against Zoroastrianism from one of the prominent people of his time, Fyodor Momsuetsky. At the same time, he goes to the region of Gokhtn, located in close proximity to Persia and, therefore, more susceptible to its influence. In this regard, A. Martirosyan in his book comes to the following conclusion: “Mashtots leaves the court not out of disappointment, but with a very definite intention - to organize resistance against the growing Persian influence, the strengthening of Zoroastrianism in the part of divided Armenia that came under Persian rule” - and further concludes: “Thus, although Mashtots began his preaching work for the sake of spreading Christianity, however, with the clear intention of fighting against Zoroastrianism, Christianity had already taken root in Armenia and existed as a state religion for a whole century, so there seemed to be no special need to preach Christianity - if not for this question.

Christianity had to be given a special direction, to be aroused against Zoroastrianism, a doctrine whose bearer was the hostile Persian state. Religious teaching was turning into a weapon." Having ebullient energy, Mashtots saw that his efforts in preaching were not giving the result that he would like. An additional means of struggle was needed. This means should have been national literature. According to Koryun, after the mission to Goghtn Mashtots “conceived to take even more care of the consolation of the whole country, and therefore multiplied his continuous prayers, with open hands (raising) prayers to God, shed tears, remembering the words of the apostle, and said with concern: “Great is the sorrow and incessant torment of my heart for my brothers and relatives..."

So, besieged by sad worries, as if in a network of thoughts, he was in the abyss of thoughts about how to find a way out of his difficult situation. It was at this time, apparently, that Mashtots had the idea of creating an alphabet. He shares his thoughts with Patriarch Sahak the Great, who approved his thought and expressed his readiness to help in this matter.

It was decided to convene a council so that the highest clergy would approve the idea of creating a national alphabet. Koryun states: “For a long time they were engaged in inquiries and searches and endured many difficulties, then they announced the constant search for their Armenian king Vramshapuh.” The king, who had previously been outside the country, upon returning to Armenia, found Sahak the Great and Mashtots together with the bishops, concerned about finding the Armenian alphabet. Here the king told those gathered that while in Mesopotamia, he learned from the priest Abel a certain Syrian bishop Daniel, who had Armenian letters. This Daniel seemed to have unexpectedly found the forgotten old letters of the Armenian alphabet. Having heard this message, they asked the king to send a messenger to Daniel so that he would bring them these letters, which was done.

Having received the desired letters from the messenger, the king, together with Catholicos Sahak and Mashtots, were very happy. Youths from all places were gathered to learn new letters. After their training, the king ordered that the same letters be taught everywhere.

Koryun narrates: “For about two years, Mashtots was teaching and taught classes in these scripts. But... it turned out that these scripts were not sufficient to express all the sounds of the Armenian language.” After which these letters are discarded.

This is the history of the so-called Daniel letters, which, unfortunately, were not preserved in the chronicles and therefore cause a lot of misunderstandings among scientists. Firstly, the dispute is about the meaning of the phrase “suddenly found”. Were these really “forgotten Armenian letters” or did he confuse them with Aramaic (in the letter the words Armenian and Aramaic are written almost identically in Syriac). R. Acharyan believes that this could be an ancient Aramaic letter, which was no longer used in the 4th-5th centuries. These are all assumptions that do not clarify the picture. The very interesting hypothesis about S. Muravyov’s Danilov letters, which will be discussed later, did not clarify the picture either.

Let’s leave Daniel’s letters, to which we will return, and follow Mashtots’ further actions. Movses Khorenatsi narrates that “Following this, Mesrop himself personally goes to Mesopotamia, accompanied by his disciples to the mentioned Daniel, and, not finding anything more from him,” decides to independently deal with this problem. For this purpose, he, being in one of the cultural centers - in Edessa, visits the Edessa Library, where, apparently, there were ancient sources about writing, about their principles of construction (this idea seems convincing, since in principle, proposed for trial readers, the oldest view is seen in the writings). After searching for a certain time for the necessary principle and graphics, Mashtots finally achieves his goal and invents the alphabet of the Armenian language, and, adhering to the ancient secret principles of creating alphabets, he improved them. As a result, he created an original, perfect alphabet both from the point of view of graphics and from the point of view of phonetics, which is recognized by many famous scientists. Even time could not significantly affect him.

Mashtots describes the very act of creation of the Khorenatsi alphabet in his “History” as follows: “And (Mesrop) sees not a vision in a dream or a waking dream, but in his heart, with pre-spiritual eyes presenting to him the right hand writing on a stone, for the stone kept the markings, like footprints in the snow. And not only (this) appeared to him, but all the circumstances were collected in his mind, as in a certain vessel." Here is an amazing description of Mashtots' moment of insight (it is known that insight accompanies a creative discovery that occurs at the moment of the highest tension of the mind). It is similar to cases known in science. This description of a creative discovery that occurs at the moment of greatest tension of the mind through insight is similar to cases known in science, although many researchers have interpreted it as a direct divine suggestion to Mesrop. A striking example for comparison is the discovery of the periodic table of elements by Mendeleev in a dream. From this example, the meaning of the word “vessel” in Khorenatsi becomes clear - this is a system in which all the letters of the Mesropian alphabet are collected.

In this regard, it is necessary to emphasize one important idea: if Mashtots made a discovery (and there is no doubt about this) and the entire table with letters appeared before him, then, as in the case of the periodic table, there must be a principle connecting all the letter signs into a logical system. After all, a set of incoherent signs, firstly, is impossible to open, and, secondly, does not require a long search.

And further. This principle, no matter how individual and subjective it may be, must correspond to the principles of constructing ancient alphabets and, therefore, reflect the objective evolution of writing in general and alphabets in particular. This is precisely what some researchers did not take into account when they argued that Mashtots’s main merit was that he revealed all the sounds of the Armenian language, but graphics and signs have no meaning. A. Martirosyan even cites a case when the Dutch scientist Grott asked one nine-year-old girl to come up with a new letter, which she completed in three minutes. It is clear that in this case there was a set of random signs. Most people can complete this task in less time. If from the point of view of philology this statement is true, then from the point of view of the history of written culture it is wrong.

So, Mashtots, according to Koryun, created the Armenian alphabet in Edessa, arranging and giving names to the letters. Upon completion of his main mission in Edessa, he went to another Syrian city of Samosat, where he had previously sent some of his students to master the Greek sciences. Koryun reports the following about Mashtots’ stay in Samosat: “Then... he went to the city of Samosat, where he was received with honors by the bishop of the city and the church. There, in that same city, he found a certain calligrapher of Greek writing named Ropanos, with the help of whom designed and finally outlined all the differences in letters (letters) - thin and bold, short and long, separate and double - and began translations together with two men, his disciples... They began translating the Bible with the parable of Solomon, where at the very beginning he (Solomon) offers to know wisdom."

From this story, the purpose of visiting Samosat becomes clear - the newly created letters had to be given a beautiful appearance according to all the rules of calligraphy. From the same story we know that the first sentence written in the newly created alphabet was the opening sentence of the book of proverbs: “Know wisdom and instruction, understand sayings.” Having finished his business in Samosat, Mashtots and his students set off on the return journey.

At home he was greeted with great joy and enthusiasm. According to Koryun, when the news of the return of Mashtots with new writings reached the king and the Catholicos, they, accompanied by many noble nakharars, set out from the city and met the blessed one on the banks of the Rakh River (Araks - S.B.). "In the capital - Vagharshapat this joyful the event was solemnly celebrated.

Immediately after returning to his homeland, Mashtots began vigorous activity. Schools were founded with teaching in the Armenian language, where young men from various regions of Armenia were accepted. Mashtots and Sahak the Great began translation work, which required enormous effort, given that they were translating fundamental books of theology and philosophy.

At the same time, Mashtots continued his preaching activities in various regions of the country. Thus, with enormous energy, he continued his activities in three directions for the rest of his life.

This is the brief history of the creation of the Armenian alphabet.

ARMENIAN LANGUAGE, language spoken approx. 6 million Armenians. Most of them are residents of the Republic of Armenia, the rest live in the diaspora over a vast territory from Central Asia to Western Europe. More than 100,000 Armenian speakers live in the United States.

The existence of Armenia was attested several centuries before the appearance of the first written monuments (5th century AD). The Armenian language belongs to the Indo-European family. The place of Armenian among other Indo-European languages has been the subject of much debate; it has been suggested that Armenian may be a descendant of a language closely related to Phrygian (known from inscriptions found in ancient Anatolia). The Armenian language belongs to the eastern (“Satem”) group of Indo-European languages, and shows some commonality with other languages of this group - Baltic, Slavic, Iranian and Indian. However, given the geographical location of Armenia, it is not surprising that the Armenian language is also close to some Western (“centum”) Indo-European languages, primarily Greek.

The Armenian language is characterized by changes in the field of consonantism. which can be illustrated by the following examples: lat. dens, Greek o-don, Armenian a-tamn "tooth"; lat. genus, Greek genos, Armenian cin "birth". The advancement of stress on the penultimate syllable in Indo-European languages led to the disappearance of the overstressed syllable in Armenian; Thus, the Proto-Indo-European ébheret turned into ebhéret, which gave ebér in Armenian.

As a result of centuries-old Persian domination, many Persian words entered the Armenian language. Christianity brought with it Greek and Syriac words; The Armenian lexicon also contains a large proportion of Turkish elements that penetrated during the long period when Armenia was part of the Ottoman Empire; There are a few French words left that were borrowed during the Crusades. The grammatical system of the Armenian language preserves several types of nominal inflection, seven cases, two numbers, four types of conjugation and nine tenses. Grammatical gender, as in English, has been lost.

The Armenian language has its own alphabet, invented in the 5th century. AD St. Mesrop Mashtots. One of the first monuments of writing is the translation of the Bible into the “classical” national language. Classical Armenian continued to exist as the language of the Armenian Church, and until the 19th century. was the language of secular literature. The modern Armenian language has two dialects: Eastern, spoken in Armenia and Iran; and western, used in Asia Minor, Europe and the USA. The main difference between them is that in the Western dialect a secondary devoicing of voiced plosives occurred: b, d, g became p, t, k.

ARMENIAN LANGUAGE, language spoken approx. 6 million Armenians. Most of them are residents of the Republic of Armenia, the rest live in the diaspora over a vast territory from Central Asia to Western Europe. More than 100,000 Armenian speakers live in the United States.

The existence of Armenia was attested several centuries before the appearance of the first written monuments (5th century AD). The Armenian language belongs to the Indo-European family. The place of Armenian among other Indo-European languages has been the subject of much debate; it has been suggested that Armenian may be a descendant of a language closely related to Phrygian (known from inscriptions found in ancient Anatolia). The Armenian language belongs to the eastern (“Satem”) group of Indo-European languages, and shows some commonality with other languages of this group - Baltic, Slavic, Iranian and Indian. However, given the geographical location of Armenia, it is not surprising that the Armenian language is also close to some Western (“centum”) Indo-European languages, primarily Greek.

The Armenian language is characterized by changes in the field of consonantism. which can be illustrated by the following examples: lat. dens, Greek o-don, Armenian a-tamn "tooth"; lat. genus, Greek genos, Armenian cin "birth". The advancement of stress on the penultimate syllable in Indo-European languages led to the disappearance of the overstressed syllable in Armenian; Thus, the Proto-Indo-European ébheret turned into ebhéret, which gave ebér in Armenian.

As a result of centuries-old Persian domination, many Persian words entered the Armenian language. Christianity brought with it Greek and Syriac words; The Armenian lexicon also contains a large proportion of Turkish elements that penetrated during the long period when Armenia was part of the Ottoman Empire; There are a few French words left that were borrowed during the Crusades. The grammatical system of the Armenian language preserves several types of nominal inflection, seven cases, two numbers, four types of conjugation and nine tenses. Grammatical gender, as in English, has been lost.

The Armenian language has its own alphabet, invented in the 5th century. AD St. Mesrop Mashtots. One of the first monuments of writing is the translation of the Bible into the “classical” national language. Classical Armenian continued to exist as the language of the Armenian Church, and until the 19th century. was the language of secular literature. The modern Armenian language has two dialects: Eastern, spoken in Armenia and Iran; and western, used in Asia Minor, Europe and the USA. The main difference between them is that in the Western dialect a secondary devoicing of voiced plosives occurred: b, d, g became p, t, k.

Armenians- one of the oldest peoples in the world. At the same time, the question of their origin is still considered controversial in the scientific community. And unscientific versions exist, each more exotic than the other!

For example, from Bible it follows that the Armenians trace their ancestry back to Japheth- one of the sons But I. By the way, "Old Testament genealogy" makes Armenians and Jews related who also consider themselves descendants of the only righteous man on earth. The Armenian historiographers themselves, until the 19th century, had a popular theory according to which the ancestors of the people were a certain Haik- a titan who won a fierce battle Bela, one of the tyrants Mesopotamia. Ancient sources claim that the beginning of the Armenian original civilization was laid by one of the participants in the famous mythological expedition of the Argonauts Armenos of Thessaly. And some scientists believe that the roots of Armenians go back to the Middle Eastern state Urartu.

From the point of view of modern ethnography, the most likely theory seems to be that the proto-Armenian people formed around the 6th century BC on the basis of several people who mixed in the Armenian Highlands Indo-European And Middle Eastern tribes (among which there are Phrygians, Hurrians, Urartians And Luwians).

The unique Armenian language

Scientists had to rack their brains about Armenian language: all attempts by linguists to attribute it to any language group did not bring results, and then it was simply allocated to a separate group Indo-European language family.

Scientists had to rack their brains about Armenian language: all attempts by linguists to attribute it to any language group did not bring results, and then it was simply allocated to a separate group Indo-European language family.

Even the alphabet, invented in the 4th century AD by the translator Mesrop Mashtots, is unlike any of those known to us today - it traces the alphabetical nuances of ancient Egypt, Persia, Greece and Rome.

By the way, among many other ancient languages that became “dead” over time (Latin, ancient Greek), ancient Armenian is still alive - reading and understanding the meaning of old texts, knowing modern language, is not so difficult. This helps scientists parse ancient manuscripts without any problems.

A curious feature of the Armenian language is the absence of a category of grammatical gender in it - both “he” and “she” and “it” are designated by one word.

Armenians in Russia

Despite the fact that there are at least 14 million Armenians around the world today, only 3 million of them live directly in the state of Armenia.

Among the main countries of settlement are Russia, France, the USA, Iran and Georgia. Some of the assimilated Armenians even live in Turkey, and this despite the Armenian genocide that occurred in this country more than a hundred years ago.

In Russia, according to the chronicles, Armenians first appeared in the 9th century AD, in Moscow - since 1390. In Rus', Armenians were mainly engaged in crafts and trade, connecting their new homeland with the countries of the East through international merchant relations.

It is interesting that after their expulsion from Crimean peninsula Empress Catherine II, Armenians in Russia even founded their own special city - Nakhchivan-on-Don, which only in 1928 became part of the expanding Rostov-on-Don.

Cultural and festive traditions of Armenians

Armenia is considered one of the first countries, and many argue that it was the very first, that officially, at the state level, adopted Christianity: during the reign of King Trdat III, in 301. Already a hundred years after this, the Bible was translated into Armenian, and another hundred years later, the Armenian Apostolic Church actually separated its cultural religious tradition from Byzantine dogmatics. The autocephaly (that is, independence) of the Armenian church laid the foundation for popular ideas about the chosenness of the entire Armenian people.

However, like the Russians, despite such an ancient involvement in the religious Christian tradition, echoes of the pagan heritage remain in the everyday life of many Armenians.

Armenian "brothers" Maslenitsa, Palm Sunday And Ivan Kupala Day - Terendez(festival of farewell to winter), Tsarzardar(on this day, in honor of spring, people go to church with willow branches) and Vardavar(celebrations of water pouring in August).

The wedding still occupies a very important place in traditional rituals: it is nationally unique even among the most " Russified"Armenians

During the preparatory period, young people choose a matchmaker ( midjnord keen), whose duty is to persuade the girl’s parents to marry. Only after this do the relatives of the future husband (matchmakers) come to meet the bride, and, according to the ritual, they have to persuade the bride and her parents twice. After these ceremonies have been observed, the time comes engagement.

The engagement itself turns into a mini-holiday: on a certain day, relatives of the two families gather at the groom’s house, with luxurious jewelry gifts for the bride. After a short but plentiful feast, the guests go to the house of the parents of the future wife, where, immediately after the performance of the bride’s ritual dance “Uzundara,” the groom’s ritual “taking away” of his beloved away from her father’s house takes place.

But all this is just a hint to the fairy tale itself - the triumph itself, which amazes even the most developed imagination. On the appointed day (preferably in the fall or early winter), a huge number of guests, including honorary ones, gather in the groom’s house. The ceremony is conducted by the host - makarapet, a man whom everyone gathered during the evening obeys unquestioningly. And under his leadership, dancing, singing and exciting wedding competitions do not stop for a minute. By the way, the more musicians there are at the wedding, the more fun the holiday will be and the happier the life of the newlyweds will be!

The fun is also enhanced by the skill of winemaking, another traditional art of this people. The Armenians believe that excellent wine has been made by their ancestors since the time of Noah himself, and since the 19th century, winemakers have also added famous Armenian cognac.

The fun is also enhanced by the skill of winemaking, another traditional art of this people. The Armenians believe that excellent wine has been made by their ancestors since the time of Noah himself, and since the 19th century, winemakers have also added famous Armenian cognac.

However, there are practically no drunk people at weddings: Armenians not only love to drink, but also know how to drink.